British analysts: Belarus among the most dangerous states for business

- 31.12.2013, 16:48

- 3,217

Consulting company Maplecroft advises investors not to work in Belarus.

A significant increase in conflict, terrorism and regime instability in MENA (Middle East and North Africa), along with intensifying political violence and resource nationalism in East Africa, are among the key factors driving a global rise in political risks for investors, according to the sixth annual Political Risk Atlas (PRA) by global risk analytics company Maplecroft.

In addition, the PRA reveals that the potential for societal unrest to exacerbate political instability is heightened in countries such as Bangladesh, Belarus, China, Kazakhstan, Saudi Arabia and Viet Nam. This is due to the erosion of democratic freedoms, increasing crackdowns on political opposition and the brutality by security forces towards protesters, compounded by rising food prices and worsening working conditions.

Maplecroft’s Political Risk Atlas 2014 (PRA) includes 52 indices developed to enable companies and investors to monitor the key political issues and trends affecting the business environment of 197 countries. The Atlas includes both dynamic political risks, which focus on short-term challenges, such as rule of law, political violence, the macroeconomic environment, resource nationalism and regime stability, as well as structural long-term political risks, such as economic diversification, resource security, infrastructure quality, societal resilience and the human rights landscape, all which are essential ingredients of a country’s long term growth environment.

Since 2010, almost 10% of countries worldwide have seen a significant increase in the level of dynamic political risk – with foreign investors facing increased risks of political violence, resource nationalism and expropriation.

Following the Arab Awakening, Syria has experienced the most significant decline in Maplecroft’s Political Risk (Dynamic) Index, dropping from 44th in 2010 to 2nd in the 2014 ranking, above only Somalia (1st). For the first time, Egypt is categorised as ‘extreme risk’ for political violence, contributing to a fall from 27th in 2013 to 15th in this year’s overall ranking. Post-coup violence and terrorist activity in the Sinai Peninsula, where attacks went up from 20 incidents of terrorism in 2011-2012, compared to 105 incidents in the period 2012-2013 are largely responsible for the increase in Egypt’s risk. Mali (22nd compared to 40th in 2013), and Mozambique (63rd compared with 79th) also experienced significant increases in risk, primarily driven by a dramatic rise in political violence.

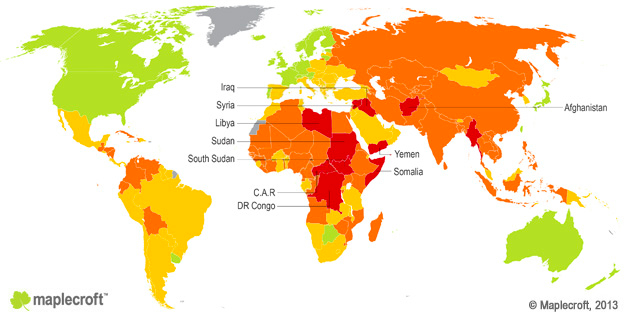

Maplecroft predicts that the situation in Syria (2nd), Libya (8th) and Egypt (15th) is now so bad that these countries will be mired in exceptionally high levels of dynamic political risk for years to come. This ‘vicious circle’ reflects the self-reinforcing impact of extremely poor governance, conflict, high levels of corruption, persistent regime instability and societal dissent and protest. Illustrating this point, seven of the worst countries for political risk – Somalia (1st), Afghanistan (3rd), Sudan (4th), DR Congo (5th), Central African Republic (6th), South Sudan (9th) and Iraq (10th) – have stayed among the bottom 10 in the Political Risk Atlas for the last six years.

Over the last year, 18 countries saw a significant rise in political violence, with East Africa host to the largest proportion of these. In Maplecroft’s Political Violence Index, high levels of conflict and terrorism saw Kenya ranked 24th most at risk, while significant increases in risk in Eritrea (ranked 35th in 2014 compared with 43rd in 2013), Tanzania (61st compared with 77th) and Mozambique (62nd compared with 101st), contributed to East Africa overtaking Central Africa as the highest risk region for political violence in sub-Saharan Africa. Maplecroft also expects Kenya’s risk profile to worsen over the next year due to its security situation, which was evidenced by the al Shabaab terrorist attack on the Westgate shopping centre in Nairobi, where at least 67 people died.

East Africa’s dynamic political risk profile for 2014 is further intensified by a significant increase in the likelihood of ‘soft’ resource nationalism, which has pushed the regional average from ‘medium’ to ‘high risk’ over the past year. This score change reflects a substantial increase in mining royalties in Kenya (ranked 41st in the Resource Nationalism Index 2014) and the planned imposition of capital gains taxes in Mozambique (43rd). This, coupled with the trend of increased political violence, presents significant operational challenges for business at a time when investors are increasingly looking to the region following the discovery of substantial oil and gas reserves.

Globally, over the last year, the risk of resource nationalism has increased in 15% of countries due in part to governments attempting to offset the risk of societal unrest through populist policies funded by ‘creeping’ resource nationalism, i.e. through taxes and local content requirements) or through outright expropriation. Maplecroft identifies Indonesia (24th), Brazil (70th), India (97th) and South Africa (109th) as countries to watch in 2014, as national elections increase the likelihood of resource nationalist rhetoric and policies.

“The trend of increased dynamic political risk is largely driven by longer-term societal challenges, such as threats to human security and the undermining of political freedoms by oppressive regimes,” states Maplecroft CEO Professor Alyson Warhurst. “This increases the potential for societal unrest and instability, particularly in countries with high levels of social gains, such as education and IT literacy, among a disenfranchised youth.”

Countries categorised as ‘extreme risk’ in Maplecroft’s Oppressive Regimes Index increased from 16% in 2011 to 23% in 2014. More than 50% of countries are now categorised as ‘extreme’ or ‘high risk’ in this index – a source of significant concern for foreign investors that may become complicit with the actions of these regimes or face disruption to business continuity as a result of societal unrest. The countries with the most significant disparity betweenpolitical freedoms and social gains, with the highest potential for societally forced regime change, are Uzbekistan (ranked 8th inthe Oppressive Regimes Index), China (9th), Saudi Arabia (11th) Turkmenistan (12th), Belarus (16th), Cuba (22nd), Bahrain (24th), Viet Nam (25th), Kazakhstan (32nd) and UAE (42nd).

Whether the potential for societally induced regime change or instability is realised depends largely on the entrenched power of government; its willingness and ability to use force; and the extent and speed of policy reform. According to Maplecroft, the speed of policy reform in China – categorised as ‘extreme risk’ in the Oppressive Regimes Index – is likely to be sufficient to limit the chances of widespread societal unrest leading to a “Jasmin” revolution. In contrast, the Viet Nam government has responded to growing opposition by cracking down on social media and freedom of speech, moves that may undermine long-term regime stability.

The PRA 2014 also illustrates positive upward trends in a number of key growth markets, highlighting opportunities for investors. The Philippines (which improved from 19th highest risk in the 2011 index to 35th in the 2014 index), India (26th to 47th), Uganda (29th to 50th), Ghana (84th to 106th), Israel (99th to 118th) and Malaysia (101st to 122nd) all experienced a significant decrease in the level of dynamic political risk over the past four years. This steady improvement, in part, reflects a fall in political violence in the Philippines, India and Uganda, while Malaysia and Israel experienced significant improvements in the level of governance. A positive business and macroeconomic environment also helped to lower the overall level of risk in these key economies. However, the vulnerability of many key growth economies to external shocks can impact levels of political risk, as illustrated by Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines.